Every third medical student struggles with alcohol abuse or dependence, according to a national study conducted nearly 10 years ago. But are there strong systems in place to support trainees trying to break the vicious cycle of substance use disorders and seek help?

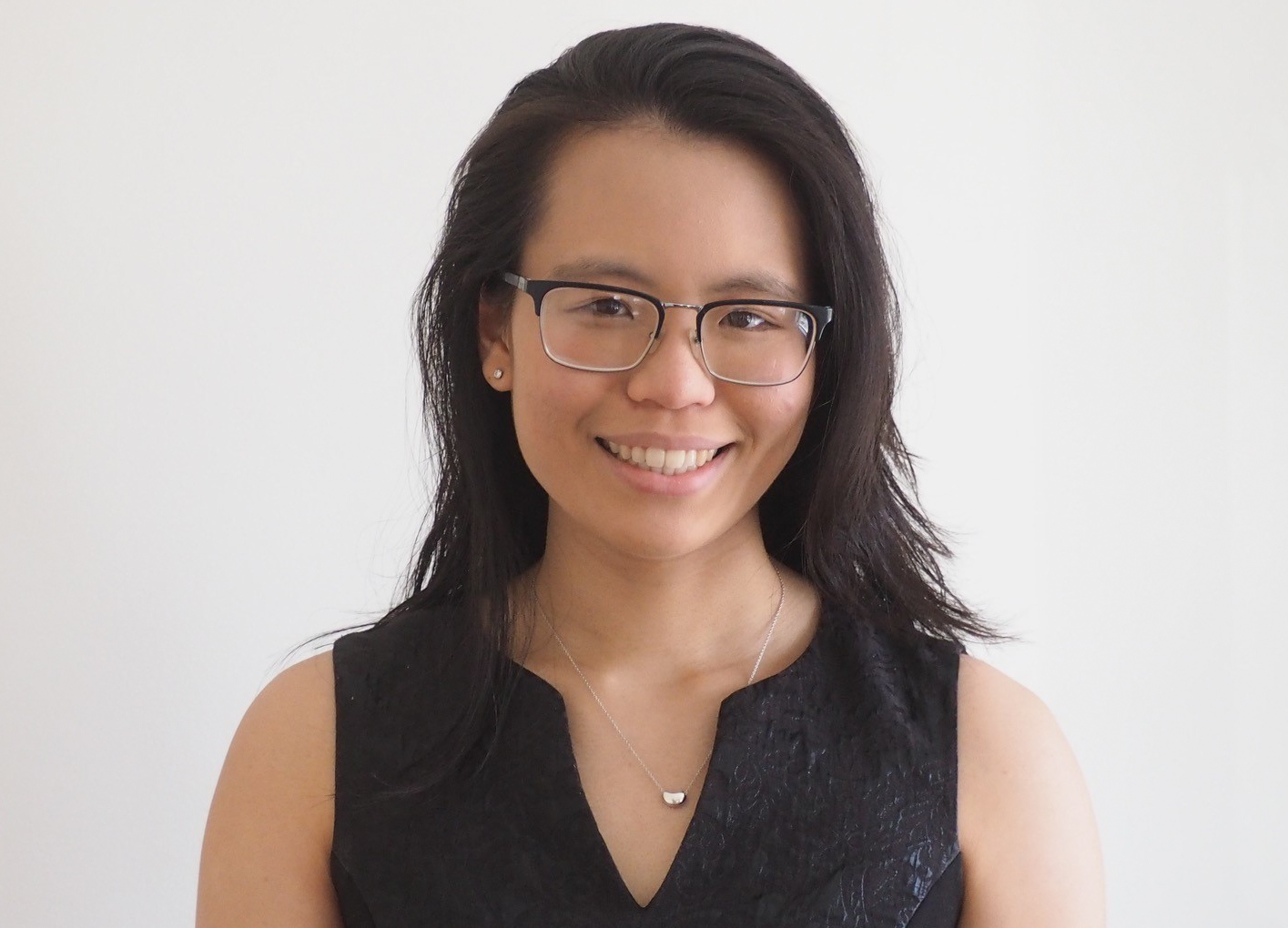

In a research letter published in JAMA Psychiatry today, a group of medical students and physicians, led by University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine M.D.-Ph.D. student Philip Mannes and UPMC Internal Medicine-Pediatrics resident Dr. Tiffany Wang, found that only 1 of 111 medical schools in their independent survey had published sufficient guidelines for managing substance use disorders and provided appropriate support to students seeking help.

Philip Mannes

“Substance use remains a sensitive topic, but it’s important to acknowledge the prevalence of concerning use, dependency and substance use disorders in physicians and physician trainees,” said Mannes. “Luckily, success rates for treating substance use disorders in physicians are very high, and in the same way, it’s important to prioritize and treat students who will one day be treating patients.”

Following the troubling reports of high rates of alcohol and prescription medicine abuse among doctors, many medical organizations across the nation took great pains to provide support and education. Nowadays, physicians in nearly every state can access treatment through physician health programs, which coordinate care and management of substance use disorder and ensure successful relapse-free recovery in the vast majority of referred individuals.

Similar advocacy has not been provided to medical students.

Dr. Tiffany Wang

In the early 1990s, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) published guidelines offering a framework to aid medical schools in developing policies concerning student substance use. While the AAMC encourages schools to develop policies in accordance with the published recommendations, medical schools are not mandated to follow them.

The AAMC guidelines emphasize promoting professional educational and prevention programs and removing the stigma associated with substance use disorder by recognizing it as a treatable disease that affects all of society. The guidelines also stress the importance of confidentiality for individuals throughout the treatment process and providing students with support to continue their education.

To assess medical schools’ adherence to the six AAMC-endorsed guidelines, the authors reviewed student handbooks for published substance use policies.

All but a quarter of handbooks met fewer than one criterion in the AAMC guidelines, and only one school met all six. While nearly all schools mentioned referrals to mental health services, only a few explicitly stated their commitment to promoting a successful environment to finish training and ensuring that history of substance abuse will not affect students’ evaluations.

“The systems should change to promote prevention and treatment as opposed to punishment,” said Wang. “We hope that our analysis encourages more reflection about existing substance abuse policies in medical schools and leads to a more student-centered approach in managing unhealthy substance use for medical students.”